One month after

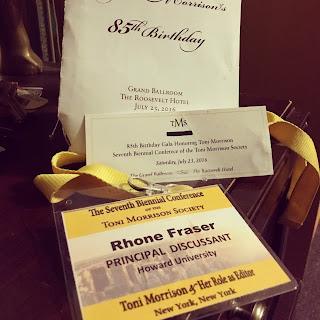

being invited as a Principal Discussant to the Toni Morrison Biennial organized

by the Toni Morrison Society, I still cherish that experience.

My experience at the biennial reminded me of

the importance of maintaining the balance between male and female

energies. I was honored to meet the

editor of Toni Morrison, Errol McDonald.

I thought I remembered reading that McDonald edited Beloved and Jazz. When I was able to ask him about this, he

replied that he did not edit Beloved, but

he edited Paradise and Love. I wanted to ask him more questions about what it was like to edit

the fiction of Toni Morrison, but I was very conscious of my time and the time

of the brilliant people and brilliant energies that I was around. Angela Davis was at this conference and

shared that the book Morrison edited, Angela

Davis: An Autobiography, was written in the hills of Santiago de Cuba. “She convinced me that the book she was going

to publish was the book I wanted to write.

I spent six weeks in the mountains of Santiago de Cuba…in virtual

solitude with about 700 typewritten pages.”

I learned a lot in the breakout roundtable discussions on the second,

third, and fourth days of the biennial.

On the roundtable discussion on the first day, I learned a lot from

Faraha Norton who, like Professor Morrison, worked at Random House and saw

first hand the reality of “institutionalized racism,” which was a term coined

by Morrison’s editing that gained credence in Black Power:

The Politics of Liberation written by Kwame Ture and Charles V.

Hamilton. Norton said that while

Morrison was very influential as an editor in selecting books for Random House to edit and publish,

she was still less powerful than Jason Epstein who was editorial director at

Random House. Morrison was still less powerful

than Bob Bernstein who was president and CEO of Random House. In her book The Burglary, Betty Medsger writes about how J. Edgar Hoover up

until his death made sure that authors who were even remotely sympathetic to

communism were not published.

Both

Epstein and Bernstein as publishers had supported the McCarthyist-J. Edgar

Hoover-imposed dragnet against artists.

They also supported the very destructive U.S. foreign policy in the

1970s that was carried out by Kissinger against Cambodia and Chile. By the time Morrison joined Random House, the

purge against those who challenged the mainstream status quo had already taken

place, so that any serious change brought about by ordinary citizens as a

result of book reading would be minimal.

More needs to be written on this.

I glanced at an important book by the Toni Morrison Society President

Dr. Evelyn Schreiber called Race, Trauma,

and Home in the Novels of Toni Morrison, where she included a very powerful quote

by Morrison who was interviewed by Angels Carabi: “there are certain things that

are repressed because they are unthinkable, and the only way to come free of

that is to go back and deal with them…And that makes it possible to live

completely” (51). This quote really

spoke to me and reminded me of what novelist Paule Marshall said in her 1979

interview Alexis DeVeaux: “you have to psychologically go through chaos to

overcome it” (Hall & Hathaway, eds., p.49).

I appreciated

learning from a book talk by Dr. Dana Williams about Morrison’s time at Random

House. Dr. Williams shared her research from her upcoming book Toni at Random, and talked about Professor Morrison's efforts to promote, most memorably to me, They

Came Before Columbus by Ivan Van Sertima.

Williams talked about the difficulty that Morrison had in finding Black

historians and writers who would read and provide a favorable review of this

book by Van Sertima that forcefully argued the presence of African people in

the West centuries before Columbus. I

was surprised but not so surprised to learn that Dr. John Hope Franklin was one

of those scholars who declined to review Sertima’s book. This kind of decline reminds me of how

historians can sometimes behave territorial when it comes to engaging the work

of artists and authors.

I appreciated

listening to the panel on the morning of Saturday July 23rd that featured

novelists Edwidge Danticat and Tayari Jones, both of whom I talked to briefly

in the hotel lobby about an hour before their panel. I appreciated Tayari’s point that efforts to retaliate against the Dallas police

recalls groups in Morrison’s fiction, namely her third novel Song of Solomon, and the group she

described as the Seven Days. There are a lot of similarities between Micah

Xavier Johnson and Morrison’s Guitar in Song

of Solomon. Danticat mentioned that

Gavin Long’s life is very Morrisonian in the way that he wanted to publish a

particular kind of book the way that Morrison was clear about publishing

certain kinds of books while at Random House.

On the roundtable

discussion on the second day, I learned a lot from readers of Morrison talking

about how her fictional characters use violence as language. We mentioned specifically Pauline and Cholly

Breedlove in The Bluest Eye. Lavinia Jennings who is author of the

best review written on A Mercy, and

author of Toni Morrison and the Idea of

Africa, said that in all of Morrison’s work, she shows that the three most

destructive ideas in the human mind are: romantic beauty, romantic love, and

possessive love. Marie Umeh said she

asked Morrison her message in one of her novels and Morrison’s reply was “love

nothing.” Here Morrison is challenging the

notion of “love” as presented by the white mainstream. This kind of love is a verb that is based

primarily on the amount of capital exchanged, and is ultimately shallow and

materialistic.

I saw in person

for the first time scholars of Morrison that I had not met before, especially

Susan Neal Mayberry who wrote Can’t I

Love What I Criticize: The Masculine in Morrison, which I appreciated. I especially appreciated what Mayberry said

about Sula, and how she was punished

by the Bottom community for daring to act “like a man.” This reminds me of how I think Amy Ashwood

Garvey was treated by Marcus Garvey for taking sexual liberties that her time period restricted her from taking.

Besides meeting Dr. Schreiber, Professor Mayberry, Tayari Jones, Edwidge

Danticat, and Dr. Jennings, I had a brief yet interesting conversation with

Juda Bennett about his book Toni Morrison

and the Queer Pleasure of Ghosts. I

also had an interesting conversation with Jaleel Akhtar, and was able to read

select parts of his book Dismemberment in

the Fiction of Toni Morrison. He

gets the term “dismemberment” from the Frantz Fanon whom he quotes: “Morrison’s

fiction is replete with moments of Fanonian dismemberment.” But I was most interested in the point Akhtar

made about what Morrison was saying with her Peter Downes character in A Mercy: “Peter Downes sells the

argument of Africans-selling-Africans under the garb of a disguised apology in

order to convince Vaark: “Africans are interested in selling slaves…as an

English planter is in buying them.” In

my research, I found that this is something that Amy Ashwood Garvey discovers

first hand in her 1947 trip to the Gold Coast when researching the descendants

of her great grandmother, Grannie Dabas.

Part of this

biennial included an authors and editors luncheon which included a very very

inspiring talk by Chris Jackson, who is vice president and executive editor of

One World/Random House. Jackson edited Between the World And Me by Ta-Nehisi

Coates and is editing his next book. He

seems to replace the editorial role that Morrison played at Random House. When I read this, I immediately remembered

the One World logo that was on a lot of books, especially The Autobiography of Malcolm X As Told To Alex Haley and the

important function of imprints. This

also made me think of Elizabeth Nunez’s fictional exploration into the dynamics of

imprints in her very important 2011 novel Boundaries,

that I am now writing an article about.

In Chris Jackson’s luncheon talk, he said that “Toni Morrison is the

reason I do the work that I do.” He said

that he grew up in New York raised by a single mother and deeply steeped in the

religious tradition of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

He also spent some time writing the publications of the Jehovah’s

Witnesses. What I found interesting

about his time writing their publications was how the funders ignored editorial

staff and vice versa. This provides an

amazing potential for the editorial staff to promote ideas that contradict and

subvert the worldview of the funders. J.

Edgar Hoover spent decades policing the editorial staff of all mainstream publishers

so that the funders’ worldviews never contradicted the worldviews of the

editorial staff. Jackson’s observation

of how the editorial staff at the Jehovah’s Witness publications ignored the

funders of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, reinforced his contempt for

capitalism. He also said that book

publishing is a business and part of the job is to be aware of the market. Even though one is aware of the market, the

most important lesson I got from his lecture is that “one should never

compromise one’s values for the values of the funders.” He said that the status quo is often a paper

tiger, and that mission oriented book publishing is at the end of the day,

despite the paper tiger, still sustainable.

I appreciated how

Chris Jackson recognized Ishmael Reed as an institution builder. Jackson noted how Reed started the Before

Columbus Foundation which gives the American Book Award. I was grateful to witness novelist Marlon

James earn the 2015 American Book Award for his novel about the forgotten

Jamaican youth called A Brief History of

Seven Killings. I met Karen from the

Cleveland Foundation’s Anisfield-Wolf Book Award who told me that they awarded

Marlon James with an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.

This novel is a must read.

Jackson finished his talk underscoring the reality that mission based

publishing requires faith in the work and an understanding of the

audience.

My entire

experience I believe was embodied by what Morrison herself said in her essay “Rootedness:

the Ancestor as Foundation” about the importance of maintaining the balance

between male and female energies. At one

point in this essay, she described the diminishing of one of her character’s,

Reba’s abilities, because of “the absence of men in a nourishing way” in this

character’s life. Morrison later says

that her character Pilate represents “the best of that which is female and the

best of that which is male” (1071). She was later asked about developing a

specific Black feminist model of critical inquiry, to which she replied that

she thinks “there is more danger in it than fruit, because any model of criticism

or evaluation that excludes males from it is as hampered as any model of

criticism of Black literature that excludes women from it.”

Attacks Against Nate Parker

The way I see the

world after attending this biennial reminds me of the ways that white

mainstream society continues to try to promote “a Black feminist model of

inquiry” uniquely dedicated to silencing the artistic work of Black men. “A Black feminist model of inquiry” in and of

itself does not normally silence the artistic work by Black men, however the

shallow, flighty way it is being used by hack writers like Roxane Gay, Ibram

Rogers, and most recently by Michael Arcenaux, to silence the work of Nate

Parker is dangerous, destructive, only aids “the absence of men in a nourishing

way” which ultimately empowers the white mainstream.

If these hack writers cared anything about

the rape culture that they claim Parker promotes by his public response to his

1999 case, they would apply the same moral expectation and standard they expect

from Nate Parker to Roger Ailes. To Jeffrey

Epstein. To Bill Clinton. To Hillary Clinton.

The white

mainstream will not enumerate the crimes against women and children that these

wealthy men have committed, however these hack writers want Nate Parker to

publicly address the verdict and settlement and within one day become a one man

poster child for the immediate destruction of Western rape culture. The attacks against the character of Nate

Parker is similar to the destruction of the work of Bill Cosby. Although Cosby is facing trial for allegations of rape, his work which promotes the opposite has literally been erased from network television and internet. Bill Cosby’s work did not promote a rape

culture against women, however in the white mainstream’s court of public

opinion, he was a certified rapist and entire younger generations should be denied

the very important moral lessons of his work. They should suffer “the absence of men in

a nourishing way.” Morrison edited George Jackson's book Blood In My Eye. In his other book Soledad Brother, Jackson called Cosby "a running dog with the fascist" for choosing to play an intelligence agent in "I Spy." Morrison's editing allowed us different perspectives of Jackson and Cosby "in a nourishing way."

At this biennial

conference, attendees received a complimentary updated copy of The Black Book, which Morrison originally

edited in 1974 and of which Morrison was inspired to write her memorable novel Beloved. Thank you to Lynne Simpson for making this

complimentary copy possible. In this

complimentary copy of The Black Book that

the publisher Knopf provided however, the epigraph that was in a previous

edition by Bill Cosby was removed from this complimentary updated copy. Toni Morrison herself spoke to the

attendees and asked a simple question: “what happened?” The removal of Cosby’s epigraph speaks to the

ways that the mainstream promotes an “absence of men in a nourishing way,”

especially the absence of Black men whose work challenges the racist status

quo.

This “absence of

men in a nourishing way” is also being promoted by hack writers who choose to

attack Nate Parker’s character.

These hack writers

hold Parker to a moral standard that they would never hold to industrialists

like the Clintons who promote and practice a rape culture that continues today in

the form of U.S. imperialism.

The shallow application

of this inquiry continues to, as Christopher Columbus did and as Bartolomeo de

las Casas wrote about in Destruction of

the Indies, divide the indigenous and their leaders like Hatuey in order to

conquer us mentally to believe that the mainstream cares anything about changing

its endemic rape culture.

Notice that all of

these hack writers (Gay, Rogers, and Arcenaux) telling their readers not to

support Parker’s upcoming film Birth of A

Nation are all writers paid by capitalists, usually liberal capitalists, dividing-and-conquering in

typical Columbus fashion. Each of these

hack writers are paid by companies profiting from the same kind of imperialism

that the work of Nat Turner was designed to destroy.

Gay wrote her

piece for the New York Times which

has made a daily practice out of promoting U.S. imperialism across the globe by

feigning concern for women’s rights while refusing to cover the rape culture

within the U.S. military (see “Colombian Report on U.S. Military Child Rapes Not

Newsworthy to U.S. News Outlets: http://fair.org/home/colombian-report-on-us-militarys-child-rapes-not-newsworthy-to-us-news-outlets-2/).

Rogers wrote his

hack piece against Parker just after publishing his latest book by NationBooks

which, like the New York Times, promotes

imperialist profit by silencing messages like Turner’s.

Arcenaux wrote his

hack piece against Parker from complex.com, founded by the apolitical fashion designer

Marc Ecko and styled by Business Insider as “Most Valuable Startups in New

York.” Startups become startups by

supporting the imperialist economy based on the chattel slavery Nat Turner’s

work intended to demolish. Complex.com would

only benefit from bashing the revolutionary message of a Nat Turner that was trying

to destroy an economy based in chattel slavery.

Arcenaux can dress his critique of Parker in fancy attire, however his

critique is still a hack job that is trying to discourage the revolutionary

message of Turner’s revolt the same way the state of Virginia was trying to do

with Nat Turner.

In their faux

concern for the U.S. rape culture that is mum on the rape culture of the U.S.

military, Gay, Rogers, and Arcenaux in their attacks against Parker promote a

shallow application of “a Black feminist model of inquiry” that promotes “the

absence of men in a nourishing way.”

These hack writers

who apply Black feminist inquiry in a shallow way and say they’re not

supporting Parker’s film in the name of “ending rape culture,” are absolutely

hypocritical. They are the same hack

writers who tell you to support Hillary because “she is the lesser of two

evils,” and promotes a rape culture in the U.S. military like Hillary and her

supporter Arcenaux did when she turned a blind eye to the U.S. Sargeant Michael

Coen’s rape of Colombian women. Arcenaux

recently tweeted that shutting down the Clinton Foundation is “a stupid idea.” This is the same foundation that like

Christopher Columbus has raped the Haitian people, stole money intended for earthquake relief, profited from promoting

Henry Kissinger’s world order and desperately tries to convince the world that

spreading “democracy” is not the same as spreading a lethal white supremacist

capitalism that is killing the earth. These are the same hack

writers who tell us that Julian Assange is a rapist, based on unsubstantiated

evidence that was doctored by government agencies desperately seeking to

discredit him. By attacking the

character of Parker, these writers are encouraging specifically the absence of

Black men “in a nourishing way,” and continue the divide and conquer strategy

used by Columbus against our people.

This is an attack that Morrison’s work is dedicated to exposing and

ending.

This is an attack that is tired

and should completely be ignored. –RF.